Students Estifa’a, Leevan and Lorenzo will soon be undertaking their research project at a partner institution overseas. These students, who have completed year 3 of their undergraduate degree, are the first of our students to embark on their research project overseas as part of the MPhys Physics with a Year Abroad degree.

Estifa’a will be working with scientists from the Canadian group, ALPHA – Canada, a group in the international ALPHA project based at CERN. This group studies the properties of antimatter atoms in order to attempt to answer some of the most fundamental questions in modern physics. Having previously successfully isolated antimatter atoms in a “magnetic bottle”, their research now focuses on studying the gravitational behaviours of these atoms, as well as using microwave spectroscopy to study the charge, parity and time reversal of anti–hydrogen atoms.

I wanted to embark on a journey that will push me outside of my comfort zone, challenge my perceptions and help me gain self-confidence. I will have the chance to meet people from diverse backgrounds in a research environment outside the UK. It was also the idea of being involved in physics research that has a real effect on our understanding of science that really excited me, as well being a part of a research team that is trying to make scientific contributions of historic importance. Estifa'a

Leevan’s work is a multi-disciplinary project with collaborations between Neuroscience, Chemistry and the Bio21 institute in Melbourne. It will focus on the use of fluorescent nanodiamonds for biological imaging.

This year abroad opportunity will provide me with the perfect platform from where I will be able to both experience what the field of medical physics research would entail and what a life would be like after university if I continued my academic work and became a researcher. Leevan

Lorenzo will be taking part in a research project at TRIUMF, which is one of the world’s leading subatomic physics laboratories, based in Canada, focusing on particle, nuclear and accelerator physics. He will be joining the DRAGON experiment, which aims at recreating and studying nucleosynthesis processes that happen within the cores of stars as a product of high energy nuclear fusion reactions.

This placement will give me the opportunity to have first-hand experience of what a career in Experimental Physics would be like, therefore potentially helping me in further career choices. Lorenzo

Scientists have discovered that UV light can ‘activate’ perchlorate under Martian environmental conditions, causing it to enhance the rate of bacterial death.

Professor Charles Cockell and Jennifer Wadsworth have discovered that perchlorate, which is a molecule that is abundant on the surface of Mars, can enhance the rate of bacterial death when 'activated'. Perchlorate is usually very stable at room temperature/colder temperatures and you have to heat it to hundreds of degrees Celsius to activate it. However, it has been shown that UV light can 'activate' it under Martian environmental conditions. They suspect the UV light causes it to decay into a different molecule which is lethal for bacteria.

The other major finding is that if you mix other components of the Martian surface (iron oxides and hydrogen peroxide) with the perchlorate, the lethal effect on bacteria is increased. This is interesting because it is generally thought that it would not be possible to activate perchlorate under Martian conditions. Astrobiologists will take this into consideration when looking for biomarkers/life on Mars.

Jennifer Wadsworth commented: "We already know the surface is probably inhospitable, so future missions might look at potential subsurface environments for life. We don’t know exactly how far the effect of UV and perchlorate would penetrate the surface layers, as the precise mechanism isn’t understood. If it’s the case of altered forms of perchlorate diffusing through the environment, that might extend the uninhabitable zone. We may have to dig a little deeper to find a potential habitable environment."

Simulations and theory indicate that the “synchronized swimming” of bacteria occurs in much sparser suspensions of the microorganisms than expected.

While being one of the most important unsolved questions in physics, the phenomenon of turbulence is not commonly associated with microorganisms.

Yet experiments on suspensions of swimming bacteria have revealed that they exhibit chaotic collective motion reminiscent of the turbulence seen around an airplane wing or in a waterfall: when the concentration of bacteria is high enough, they start to swirl around in vortex-like patterns that constantly change size and direction. The mechanism of this phenomenon is thought to be related to the mutual reorientation of bacteria in the fluid flow they create while swimming, but the precise mechanism has proven to be elusive.

In a recent paper, researchers from Lund, Cambridge and Edinburgh add another piece to this puzzle. Using theory and large-scale computer simulations, Joakim Stenhammar, Cesare Nardini, Rupert Nash, Davide Marenduzzo, and Alexander Morozov demonstrate that even at very low densities, individual microorganisms "feel" the presence of the others and their motion is thus never fully independent. As the concentration of bacteria is increased, the strength of these correlations build up to eventually form a chaotic state strongly similar to that seen in experiments.

Dr Alexander Morozov commented: "Up to now it was thought that low-density suspensions of swimming microorganisms are random and featureless, and that the correlations appear suddenly at the onset of collective motion. Surprisingly, we see measurable signs of these correlations at very low densities of microswimmers that significantly affect physical properties of the suspension."

Image gallery

Astronomers have released the largest ever map of the sky at infrared wavelengths, with over 1.5 million mega-pixels and containing nearly two billion stars and galaxies.

The largest infrared image of the sky ever taken, known as the UKIRT Hemisphere Survey, has been released today by astronomers led by Dr Simon Dye at the University of Nottingham and Professor Andy Lawrence at the University of Edinburgh.

The image is a whopping 1.5 million mega pixels and has detected nearly two billion stars and galaxies. It is the culmination of over ten years work on an international project to image the northern sky in the infrared part of the spectrum. Astronomers can search the image using an online database based in Edinburgh. Initially the survey is open to UK astronomers along with colleagues in Hawaii and Arizona, but in a year’s time it will be open to all astronomers world wide.

The image has been captured using the United Kingdom Infrared Telescope (UKIRT). This is a 3.8m telescope located near the summit of Mauna Kea, a dormant volcano on Hawaii. The telescope is dedicated to observing the sky in the infrared part of the spectrum, giving astronomers a view of the processes which shape the formation of stars and galaxies at wavelengths invisible to human eyes. The telescope uses an innovative IR Wide Field Camera developed at the Astronomy Technology Centre of the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh.

Dr Dye commented: “Releasing this image is a hugely exciting moment for astronomy. It gives the clearest view we have ever seen of the northern sky in the infrared. This is a significant milestone, providing an important database with a high legacy value for astronomers in years to come.”

Professor Andy Lawrence reflected: “The survey has already been used to find some of the most distant quasars known. I am cooking up my own projects as we speak.”

Completion of the project has been made possible by a partnership between the UK Science Technology and Facilities Council, the University of Hawaii, the University of Arizona, Lockheed Martin and NASA.

Image gallery

Rewarding pupils and giving them an insight into studying physics

The School of Physics and Astronomy and the Ogden Trust hosted an awards ceremony for the ‘School Physicist of the Year’. After an inspirational Physics talk by Professor Wilson Poon, the ceremony rewarded the most deserving high school students who are in their penultimate year, based on their progress in Physics. Twenty-three pupils from schools in Edinburgh were selected by their Physics teachers and attended the evening, along with a number of parents and teachers. The students were rewarded with a £25 National Book Token and a certificate enabling them to apply to events and programs organised by the Ogden Trust.

The event also enabled school pupils to gain a flavour of studying physics at University level. A range of academic staff, research colleagues and physics undergraduates students from the School of Physics and Astronomy shared information on their work and experience here and undertook a number of demonstrations and experiments.

"I enjoyed the event a lot, and it was an honour to be nominated by my school." School Physicist of the Year, Clifton Hall School

"This is a great scheme to get more of our exceptional students interested in studying Physics." C. Fergusson, Physics Teacher, Musselburgh Grammar School

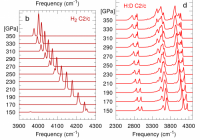

Edinburgh student Ioan-Bogdan Magdau has been awarded first place in the IoP Computational Physics Group Thesis Prize. The prestigious award is open to all UK PhD students graduating from the UK and Ireland between January 2016 and April 2017. Working with Prof. Graeme Ackland, Ioan developed a raft of codes and methods to relate quantum mechanical calculations in solid hydrogen to experimental measurements.

Although the hydrogen atom is easy to understand theoretically, when pressurized into liquid or solid state it becomes complicated. In nature, this type of matter forms the core of large planets like Jupiter and Saturn, being responsible for the planets’ large magnetic fields.

The complicated quantum mechanics of hydrogen has made it a playground for theorists, who predicted it may be a metallic, superconducting, superfluid. In the past few years, very limited experimental data from minute samples of solid hydrogen have been measured. Ignoring the “calculate what's easy to calculate'” and “look at my pretty theory” approaches to science, Ioan reverted to the classic scientific method. He tackled head on the problem of devising calculations which made predictions testable by the limited data available. Ioan's approach was characterised by always wanting to understand “What's really going on”, echoing the famous James-Clerk Maxwell's “What's the go o' that”.

Ioan's key results, confirmed in experiment, showed that high pressure warm solid hydrogen has a high symmetry, dynamic structure with half the molecules spinning and half wobbling. He also devised new methods to study isotopic mixtures of hydrogen-deuterium, showing that their spectra contain a wealth of data absent in pure hydrogen, and a far more stringent test for theory. Post-graduation, Ioan has moved to California, and taken a position at Caltech.

I am honoured to receive the recognition of the Computational Physics Group within the Institute of Physics. This award speaks not only to my hard work but also to the dedication of my advisor, Prof. Graeme Ackland and to the excellence of research conducted at the University of Edinburgh. Ioan-Bogdan Magdău

Scientists have solved a decades-old puzzle about a widely used metal, thanks to extreme pressure experiments and powerful supercomputing.

Their discovery reveals important fundamental aspects of the element lithium, the lightest and simplest metal in the periodic table. The material is commonly used in batteries for phones and computers.

A mystery of how the metal’s atoms are arranged – which influences properties such as its strength, malleability and conductivity – has been solved by their research. An international team sought to better understand lithium’s structure by studying it at cold temperatures. In this low-energy state, the fundamental properties of materials can be accurately observed.

Until now, it was difficult for scientists to explain previous experimental results indicating that lithium had a complex structure. To understand the theory properly required exceptionally accurate calculations using advanced quantum mechanics. Their latest calculations, using the ARCHER supercomputer at the University of Edinburgh, found that lithium’s structure is not complex or disordered, as previous results had suggested. Instead, its atoms are arranged simply, like oranges in a box.

Scientists suggest that in previous experiments, rapid cooling led to misleading results. To avoid those problems, they reached low-temperature conditions by placing samples of lithium under extreme pressure – up to 4,500 times that of Earth’s atmosphere – by squeezing it between a pair of diamonds. They then cooled and depressurised the sample before examining it using a synchotron device, which uses X-ray beams to see atoms.

The study, from the Universities of Edinburgh and Utah, was published in Science.

We were able to form a true picture of cold lithium by making it using high pressures. Rather than forming a complex structure, it has the simplest arrangement that there can be in nature. Professor Graeme Ackland

Our calculations needed an accuracy of one in 10 million, and would have taken over 40 years on a normal computer. Dr Miguel Martinez-Canales.

Congratulations to Dr Flaviu Cipcigan whose PhD thesis was recognised by the Institute of Physics as a leading contribution in advancing theoretical condensed matter physics.

The annual “Sam Edwards Prize”, offered by the Theory of Condensed Matter Group of the Institute of Physics, searches for the PhD thesis that contributes most strongly to the advancement of theoretical condensed matter physics. This year, University of Edinburgh student Flaviu Cipcigan received the runner-up prize. Flaviu proposed a novel method to calculate long-range intermolecular interactions between molecules and applied it to create a predictive model for the water molecule.

The prize is highly competitive, with entry open to all students from the UK and Ireland whose PhD exam took place between January 2016 and April 2017. Flaviu believes he gained an edge through strong collaboration between universities, industry and governmental labs. His PhD was part of the Scottish Doctoral Training Centre in Condensed Matter Physics, with supervision from both IBM Research and the National Physical Laboratory.

I am honoured for my thesis to be recognised as one of the top theses in the UK contributing to the advancement of theoretical condensed matter physics. It is a delight to continue a research tradition of using path integral methods in complex systems, of which Sam Edwards was one of the pioneers. This award motivates me to continue performing research of the same quality and impact. Flaviu Cipcigan

Coulomb and van der Waals forces determine the structure of water, from its crystal, through its liquid, vapour and supercritical phases. Many molecular models of water have replicated these forces using empirical functions with fixed parameters. Yet, these models do not generate realistic structures. The interaction between real water molecules is modified by the environment and thus changes character at each thermodynamic state point. A full treatment of the electronic structure is not possible, as it is beyond the capability of density functional theory and beyond the speed of accurate coupled cluster methods. Electronic structure can nonetheless be captured in an efficient yet realistic way by replacing the electrons with a simpler system: a quantum harmonic oscillator, beloved by physics undergraduates across the world. This is the core idea of electronic coarse graining, the focus of Flaviu’s thesis. Using this simple yet rich method, Flaviu created a model of water transferrable between different ice, liquid, supercooled and supercritical phases in a way that previous molecular force models are not.

Congratulations to our students who received Medals, Prizes and Scholarships at the School of Physics & Astronomy awards ceremony held on 3 April 2017.

The awards, presented by Head of School Professor Arthur Trew, gave recognition to students who achieved outstanding marks during the last academic year.

A total of 23 students received a Class Medal. Class Medals are awarded to the student with the best marks in each year of each degree programme.

Prizes and Scholarships were awarded to 11 Honours students during the ceremony, including Periklis Okalidis, who was awarded the Marion A S Ross Prize, Nichol Foundation Scholarship and Astrophysics Junior Honours Medal. Periklis is currently in year 4 of his MPhys Astrophysics degree.

Spectroscopy is often used to detect phase transitions in solids. The appearance or disappearance of a peak is regarded as evidence for a change in symmetry - a different crystal phase. This general assumption has been disproven in a recent paper by PhD student Ioan Magdau and supervisor Prof. Graeme Ackland.

Solids are held together by their electrons, so it is not expected that different isotope would have different crystal structures. For example, hydrogen and deuterium have very similar phase diagrams. However, in a recent paper it was shown that an isotopic mixture of hydrogen and deuterium had completely different Raman spectra from the pure elements. This result is so outlandish that some people assumed the experiment was flawed: different numbers of vibrational modes are a classic signature of different crystal symmetry. However, calculations in CSEC showed a different story: the disordered masses of the nuclei meant that one of the most fundamental assumptions of solid state physics, the so-called Bloch theorem - broke down. In simple terms, instead of vibrations spreading throughout the crystal as waves, they become localised on a few molecules - and the number of modes seen depends on the ways that H and D atoms can be arranged nearby, rather than the crystal symmetry.

The paper is the first all-Edinburgh study to appear in the top physics journal Physical Review Letters this year.